How I Cured My YouTube Addiction

Five curated lessons on dopamine, pain, and pleasure from Dopamine Nation by Dr. Anna Lembke.

Several months ago, while I was deeply engrossed in a YouTube binge, I stumbled upon an enlightening interview with Dr. Anna Lembke, a renowned psychiatrist and expert on addiction. She made a profound statement that jolted me out of my passive state:

“We’ve reached a tipping point where abundance itself has become a physiological stressor. So it’s not that we’re morally weak or lazy or even indulgent … It’s that the world has become a place that is mismatched for our basic neurology and physiology. And we’re trying to figure it out, but it’s super, super hard. And we’re getting sick in the process.”

Hearing this was a turning point for me. Realising that our world no longer suits our basic neurological needs struck a chord. Motivated by her insights, I read Dr. Lembke’s book, Dopamine Nation. I added it to my book review to-do lists to write about in my weekly newsletters, which happened to be this edition of Hustle Heads.

Despite dedicating 45 days and over 15,000 words to reflecting on its chapters, I found Dopamine Nation needing improvement. The scientific insights seemed too elementary, the narratives could have been more interesting, and the advice lukewarm. It felt as though I was merely testing the waters without fully committing.

Nonetheless, the book served as a significant catalyst. While its content was underwhelming, critically engaging with the text prompted me to contemplate dopamine, consumption, and the excess in our lives. Notably, it inspired me to address my YouTube addiction, which at that point had me captivated for hours, exacerbating my disengagement and sapping my drive.

Here are five key insights and an unexpected takeaway from my deep dive into Dopamine Nation, exploring the interplay between dopamine, pain, and pleasure and how understanding this relationship helped me overcome my dependence on YouTube.

Before we begin,

😞 Why Chasing Pleasure Can Make Us Miserable

In Dopamine Nation, we meet a character named David whose coping mechanism is immediately turning to medication at any sign of discomfort: Paxil for anxiety, Adderall for focus issues, and Ambien for sleeplessness. He confides to Dr. Lembke, “In the end, it came down to comfort. It was easier to take a pill than feel the pain.”

Similarly, YouTube and other streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime have been my go-to relief. These services have effectively drained my resilience, leaving me feeling detached.

However, it’s not solely about digital entertainment. Modern conveniences have conditioned me to seek instant solutions to any discomfort. I crave coffee when tired, reach for Ibuprofen when in pain, and obsessively check emails or my blog’s statistics when anxious or bored.

This raises a crucial question: Is this tendency inherently detrimental? Why should we resist comforts that seemingly enhance our immediate well-being?

Dr. Lembke points out significant issues with this approach to seeking comfort:

Dependency — The more we rely on external aids to manage our feelings, the more dependent we become. David, for instance, reached a point where he couldn't function without his dose of Adderall. Similarly, I feel restless if I haven’t scrolled through YouTube before bedtime or right after waking.

Estrangement — Constantly addressing symptoms without confronting the underlying issues can lead us to ignore our real needs. I realised that my constant desire for more content was not about the content itself but a more profound need for stimulation.

Lack of self-control — Indulging in immediate gratification makes engaging in activities that offer long-term satisfaction increasingly tricky. This hedonistic cycle suggests that while the initial indulgence is pleasurable, it often leads to feelings of emptiness, which, in turn, perpetuates the cycle.

Thus, what does this pattern tell us about the role of dopamine in our brains? Continue reading to find out.

🥱 When Nothing Feels Good Anymore

Dopamine is a crucial neurotransmitter in the brain, essential for regulating reward and pleasure centres. For instance, dopamine travels between neurons— the brain’s primary cells— reinforcing this pleasurable act when indulging in a piece of chocolate. Contrary to common belief, dopamine's role isn't directly in the sensation of pleasure but rather in the drive to seek these rewards. As Dr. Lembke describes it, it's more about "wanting more than liking". Without dopamine, while we might still find enjoyment, our drive to pursue these pleasures would diminish.

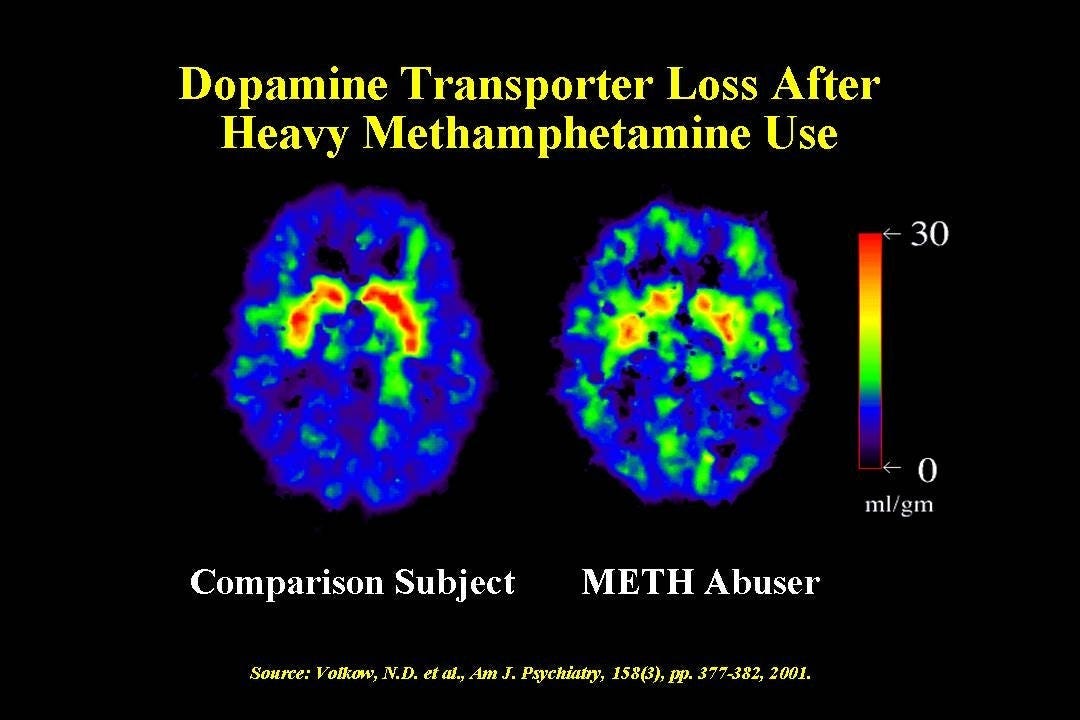

Dopamine's role in reward mechanisms allows us to assess a substance's addictive potential by how much and how quickly it triggers dopamine release in the brain. The quicker and more significant the release, the higher the addiction risk.

In her book Dopamine Nation, Dr. Lembke introduces the concept of pleasure-pain balance to illustrate how dopamine levels operate within the brain. Ideally, this balance seeks equilibrium. However, when we engage in excessive pleasure-seeking behaviours, the scale tips towards pain, leading to a compensatory increase in discomfort.

“With repeated exposure to the same or similar pleasure stimulus, the initial deviation to the side of pleasure gets weaker and shorter, and the after-response to the side of pain gets stronger and longer …”

Dr Lembke explains that repeated indulgence in similar pleasurable activities diminishes the initial pleasure over time while the resultant pain intensifies and prolongs. This ongoing cycle disrupts the equilibrium of the pleasure-pain balance, necessitating even greater indulgences to achieve the former levels of satisfaction, thereby increasing our pain sensitivity—a phenomenon known as tolerance.

For example, as my YouTube viewing escalated, so did my need for increasingly stimulating content. What began with educational videos on philosophy or documentaries quickly degenerated into less fulfilling content, constantly chasing a fleeting sense of entertainment.

This spiral of pleasure can lead to significant repercussions. Dr. Lembke notes:

“[H]eavy, prolonged consumption of high-dopamine substances lead to a dopamine deficient state.”

Such extensive engagement with high-dopamine activities can saturate the brain’s dopamine receptors, leading to anhedonia, where nothing seems enjoyable or worthwhile anymore— a state of complete disinterest and detachment. This is the dilemma faced by individuals like David, as described in the book, with his reliance on multiple medications.

Comparing the effects of high-dopamine substances like methamphetamine to my YouTube binge might seem extreme, yet it illustrates the profound emptiness and lack of motivation stemming from dopamine overload.

However, there's a silver lining.

By abstaining from these high-dopamine sources, the brain can recalibrate, restoring the pleasure-pain balance to its natural state. This recovery can rekindle our appreciation for life's more straightforward, organic pleasures, such as enjoying a meal, watching a sunset, or simply feeling the breeze against our skin.

Here's the pathway to resetting our dopamine levels.

⚖️ An 8-Step Guide to Rebalance Dopamine Levels

Anyone suggesting a dopamine detox likely has yet to research the matter thoroughly.

Detoxing implies that dopamine, a naturally occurring neurotransmitter in our body, is a toxin to be removed. However, issues arise not from dopamine itself but from excessive stimulation that leads to overproduction.

Instead of eliminating dopamine, we need to regulate its levels.

In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Lembke advocates for a 'dopamine fast', which entails abstaining from activities that trigger excessive dopamine release. Dr Lembke outlines an eight-step process known as DOPAMINE, which applies to various high-dopamine sources, not just traditional substances like alcohol.

Here's how the DOPAMINE framework unfolds and its impact on me:

D = Data: Gather information about your usage patterns. For instance, I watched YouTube videos for up to three hours daily, often when I should have been winding down or starting my day.

O = Objectives: Reflect on what the activity provides you. YouTube offered me an escape from stress and a reprieve from life's pressures, serving as an escape, painkiller, and reward.

P = Problems: Identify adverse outcomes from this usage. For me, these included brain fog, regret, and a procrastination habit at bedtime.

A = Abstinence: Cease the activity for a month. This time frame is essential for resetting the brain's reward system, though initial withdrawal can be challenging. Reflective questions like, "Do you see yourself continuing this behaviour in the long term?" can provide motivation.

M = Mindfulness: Pay attention to your thoughts and emotions during this period. Replacing one addictive behaviour with another isn't adequate; enduring and examining the discomfort is more beneficial.

I = Insight: Evaluate how abstaining has altered your perspective and behaviour. Post-abstinence, I found myself more aware and deliberate about other indulgences, leading to greater clarity and drive.

N = Next Steps: Decide whether to resume the activity and under what conditions. I experimented with controlling my engagement with YouTube, choosing content deliberately rather than impulsively.

E = Experiment: Explore what life looks like without your habitual behaviour. Finding a balance can be complex, especially when the 'drug' is something like YouTube, which is part of my part-time job.

Navigating away from addictive behaviours is challenging and goes beyond merely spelling out an acronym.

To maintain accountability and foster a sustainable lifestyle amidst constant dopamine temptations, we might consider strategies such as self-binding and actively seeking discomfort, which can rebalance our pleasure-pain thresholds.

📒 The Necessity of Self-Binding

Self-binding involves creating deliberate obstacles to prevent excessive consumption of a drug or behaviour. This concept, discussed in Dopamine Nation by Dr Lembke, is about using a moment of clarity to form a healthier long-term relationship with potentially addictive behaviours. Dr. Lembke identifies three main types of self-binding:

Physical self-binding: This strategy makes it harder to engage in high-dopamine activities, such as turning off your phone or moving it to another room.

Chronological self-binding: This method restricts usage to specific times, like allowing YouTube viewing only after 5 pm or waiting to smoke cannabis until after a work project is completed.

Categorical self-binding: This approach involves avoiding specific categories of substances or behaviours, such as adhering to a vegan diet or maintaining total abstinence from alcohol.

Given my sensitivity to visual triggers—like my phone being within sight or the YouTube icon on my display—I've found physical self-binding particularly effective. I've adopted strategies like:

Building friction: I've removed the YouTube app from my phone, switched off my phone when it's not needed, and kept it in another room while I slept.

Self-protection: I've installed blockers on my laptop and phone to prevent access to distracting apps and sites and cleared my watch history and cookies to disrupt recommendation algorithms.

While self-binding may initially feel restrictive, it ultimately empowers us. By curbing detrimental habits, we open space to focus on what truly fulfils us. Establishing these boundaries allows us to navigate a world rich in dopamine-inducing temptations with greater mindfulness and enjoyment.

👔 The Vital Discomfort of Pain-Pressing

The concept of the pleasure-pain balance is intriguing because it operates bidirectionally. While it's evident that pleasure often leads to subsequent pain, engaging in controlled painful experiences can similarly yield pleasure.

The satisfaction derived from pain-induced pleasure generally lasts longer and feels more fulfilling than the fleeting joy from immediate gratification activities high in dopamine. This explains why valuable achievements require effort and perseverance.

Consider a few examples:

Writing and publishing a novel involves years of meticulous crafting and revision.

Developing a robust and healthy relationship requires navigating challenging discussions.

Achieving a runner’s high demands rigorous physical exertion.

Activities like exercising, braving cold temperatures, and practising meditation effectively leverage this pain side of the balance. The goal is to reach a level of discomfort that is bearable and safe yet challenging enough to keep pushing your limits.

This principle also applies to managing fears and anxieties. For instance, David, a character previously mentioned, used exposure therapy to gradually face social situations, which significantly reduced his anxiety over time.

Engaging in these challenging behaviours helps me recalibrate how I handle addictive tendencies. When I start with a morning run or a cold shower, I find myself more alert, composed, and in control, contrasting sharply with the days I start by watching YouTube, which often leaves me lethargic and irritable.

Admittedly, changing these habits has been an arduous journey. Many mornings, I battle the temptation to watch one more video—a tempting voice coaxing me to indulge. However, using comparative visualisation has been instrumental. By picturing myself after indulging in quick fixes versus enduring rewarding challenges, I recognise the impact of my choices on my mental and emotional state.

This awareness of my ability to influence the pleasure-pain dynamic has been transformative, helping me make choices that align more closely with my long-term well-being.

🌯 Wrapping Up

In reflecting on Dopamine Nation by Dr. Lembke, it becomes apparent that the book overlooks a crucial aspect: not all pleasure is harmful. Many people engage with platforms like Instagram and Netflix and indulge in alcohol or sugary treats in a manner that feels balanced and healthy. They lead perfectly everyday lives, perhaps even enhanced by these pleasures.

After reading the book, I initially considered eliminating all sources of quick dopamine gratification from my life—everything from candy to the latest season of "Money Heist", coke, and fast food. However, I soon realised that wasn't quite the point.

The broader message from the book and the neuroscience of dopamine isn't to outright reject pleasure but to approach it with greater mindfulness. Life shouldn't be a harsh regime of only enduring pain and restricting ourselves. Sometimes, it's perfectly fine to enjoy a pile of candy or binge-watch series like "Friends".

Dopamine Nation promotes "Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence," suggesting that balance isn't just a steady state but can also be dynamic, fluctuating between pain and pleasure.

I maintain balance by largely avoiding YouTube, which I used to overindulge in, partly due to the guilt imposed by self-help narratives. Yet, I recognise that this restraint is part of my life's broader exploration of balance.

In a world where excess is standard, pursuing moderation can become obsessive. Therefore, in my opinion, it’s best if we approach our indulgences with moderation.

Thank you for reading.

Sanjay.

P.S. If you think my writing will be useful to your friends or family, please consider referring them to my publication.

Or if you feel like supporting my publication, you can buy me a coffee below.